Beyond museum walls: A speculative design approach to the museum of the future (2021)

︎︎︎by Jose Hopkins, Danique Hofstee, Vanessa Cantinho de JesusABSTRACT / English

Currently, museums around the worl are raising issues regarding their role. Namely, they are shifting from an approach concerning collecting, conserving and exhibiting, towards one where they can play a role as an instrument for bottom-up participation and social renewal. Inspired by theoretical frameworks like post-humanism and relational thinking, as well as digital technologies, one of the issues under scrutiny

concerns the definition and measurement of impact. Many theorists and practitioners concur that trying to find a direct causal relationship between museums and concrete impact is a limiting approach (e.g. Stone, 2001). Similarly, we believe that it can only foster limited and single, goal-oriented actions

instead of actions that are part of an ongoing change process. Following a more dynamic position, we see the future of museums as a bi-directional (or better, multiple) relationship with and within the social fabric. In this context, impact is redefined through museums becoming dialectic platforms for discussing society from within society. As they lose their absolutist stance, museums become contestants in potentia. This approach leads to a powerful activation of the social fabric, incorporating it - making it indispensable - to the point that differentiating the museum from its potential public becomes nearly

impossible. In this paper, we will review and build on some of such alternatives, particularly aided by a speculative design framework. We believe that this approach holds special power at the actual moment we are living in, within the current social and sanitary crisis. Departing from a practical research design project developed for Museum Arnhem in the Netherlands, we present an example of the potential of such an approach for the future of museums and a redefinition of impact. (https://speculative-musea.webflow.io/)

We start by proposing to conceptually rethink the museum walls, their limits as a medium. Following the ideas of Marshall McLuhan (1964), who suggested that a message’s form determines how that message is perceived and thus shaped, we speculate on novel forms to reimagine such walls. Playing with the concept of “walls as medium” we seek to contribute to the current discussions regarding how museums can alternatively understand and perform impact. From this perspective, we are able to reach an enhanced framework: one that expands the contemporary participative trend into a network-like relationship where the walls perform their medium like nature as speculative action nodes in the social fabric.

INTRODUCTION

This paper presents part of our results from the discussions, research, speculative exercises of a curator, designer, and anthropologist who met in the context of an art and design residency at Fillip Studios in the Netherlands. The main stakeholder was Museum Arnhem, which was interested in exploring the issue of impact and how to better tackle it in the context of the current changing conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Museum Arnhem saw this “new normal” as an opportunity to research and deepen their approach to how they addressed and understood their relationship to museum visitors.

Immersed in this problem, we decided to propose speculative possibilities to this problem by re-approaching a series of analyses that discussed how museums relate to their immediate public. Instead of looking for new tools to measure impact, we saw a deeper problem in how impact is theorised. We believe that a key underlying issue in the discussions addressing impact is that museums see themselves as completely (even ontologically) separated from their public. In other words, they are both fundamentally thought of as two separate entities. This has the effect of perpetuating a position where museums are continually tempted to produce and measure a one-directional and long-term kind of impact based on a cause-effect dynamic. By questioning this ontological dichotomy and proposing to see the continuities in the relationship between the museum and the social fabric instead, we set ourselves free from the discussion of the particulars of impact - such as soft vs hard indicators - and go on imagining what a networked, rhizomatic museum of the future can be. A future in which museums’ impact is not external from society, but they are both entangled. Museums and their social fabric are

interwoven.

As a vehicle to attain this idea of the continuity between the museum and th social fabric, we perform the heuristic exercise of re-thinking museum’s walls - a symbol for the separation of the museum and the public - as a medium. Aided by Marshall McLuhan theorisations, we explore the possibilities of thinking about museum walls as media. Potentially, walls are both boundaries and spatial platforms that guide the relationship between the entity they frame and their immediate context. Thus, walls as media are approached as open and dialectic platforms for making society from within society. To concretise this idea, we use a speculative design approach and present three proposals of museums’ possible futures. These proposals are meant to serve as tools for thought that may allow museums practitioners and theorists to imagine new forms of positioning themselves from within the social fabric.

This paper is structured in three sections. The first presents a brief discussion of the current debates around redefining the museum and the concept of impact. In the second section, we depart from the ontological dichotomy continuity identified in such debates to dive into the heuristic exercise of re-thinking the museum walls as a media guided by Marshall McLuhan’s thoughts. Finally, we present the speculative design approach and three design proposals we developed redefining museum walls.

SECTION 1

Re-inventing the Museum

In recent decades a body of work addressing museums and cultural institutions from a critical perspective has been emerging. Theorists and practitioners, particularly in Northern Europe, the UK and Australia, have raised questions about museums’ role and identity. For example, Carol Scott,[1]John Holden[2] and Linda Kelly[3]pointed out that some of the prominent issues have to do with the relationship between museums and their publics, the funding systems and actors that support them. Much of this conversation is triggered by the shift in seeing museums as spaces for legitimising, archiving and showcasing valuable artefacts to instruments for urban renewal, social integration and social change.[4]

The issue is not new. It has often divided opinions. It was made clear by the recent fracturing culmination of a long discussion around redefining the museum’s concept itself by the International Council of Museums.[5] After a long consulting process with members from all over the world, the proposals having a functionalist approach met with resistance from some of the partners, leading to several committee resignations. Apparently, these partners considered that defining museums around their potential to foster democratic, inclusive and polyphonic dialogues and contribute to human dignity, social justice, global equality, and planetary well-being was nothing more than an ideological statement. However, there are several examples of institutions or projects applying these values and pursuing such goals. For example, the community-driven activities promoted by the Oakland Museum[6] or an initiative by Statens Museum in trying to promote civic participation of young people[7]. Conversely, this uneasiness with the functionalist approach echoes John Holden’s ideas about the problems with a functionalist approach towards museums. According to him, understanding culture and cultural institutions only by what it can do in other areas create a state of dependency that constrains museums.[8]

What about impact?

The functionalist approach is also expressed in an equivalent change in the ideas around the impact's measurement and expectations. The increased interest in generating community well-being is influencing the impact of museums. Namely, in the fact that to measure it, demonstrate it and implement it, museums are applying quantitative indices. For instance, John Holden argues, for the UK context, that the issue is not that museums understand their impact quantitatively. The problem is that this functionalist impact is becoming the museum's most important asset.[9] He argues that privileging this functionalist approach forces institutions to show how they have contributed to the wider policy agendas, such as social inclusion, crime prevention and learning, instead of talking about what they are doing. In this sense, museums' need to act as social agents in their community (and improve people's quality of life) is instrumentalised through funding schemes. In this same vein, authors like Linda Kelly and Carol Scott show, for the Australian context, how the quality of the museum's impact is defined in terms of its economic value.[10] This means that museums have to demonstrate their relevance through quantifiable and numerical data to get public funding. Particularly for Scott, this is a problem because governments privilege this approach, thus constraining museums and jeopardise their autonomy.[11] Funding becomes the tie that binds museums to achieve the government's policy.

Additionally, we observe that Holden, Kelly and Scott's analyses reveal a fundamental aspect of museums' approach and measurement of impact influences their relationship with their social fabric. A fundamental aspect of the quantitative measurement, that comes from the functionalist approach to museums' impact reveals that museums see themselves as different or detached from their social fabric. We observe this in the quantitative approach's linear pattern. As an evidence-based and target driven decision-making process, it understands the museum's effects in a cause-effect relationship. Impact is understood as the actions of one object coming into contact with and altering another. This situation positions the museum as an independent entity that is separate from its target. In other words, this quantitative approach requires the museum to see itself as different from its social fabric. Regardless of the activity museums are implementing, if we follow Holden's critique, the quantitative approach will always demand museums to differentiate themselves from their public. If museums only apply the logics around quantifiable data, they will approach their social fabric from a distant standpoint.

On the other hand, Wendy Stone has argued that it is difficult, if not impossible, to prove that a causal relationship exists between museums and the concrete impact they generate. In this vein, Tessa Jowell points to the need for drawing attention to what culture does in and of itself. This may resonate with the aged "art for art's sake" argument or what Holden calls culture's "intrinsic value."[12] For Holden, it is urgent to look for and apply culture's intrinsic value in how museums understand their impact and value.[13] Although this argument may bring back a classist and snob approach to museums and culture in general, he sees this value as a counterbalance for the overwhelming quantitative approach.

Holden argues that art's intrinsic value can allow museums to include unmeasurable and qualitative outcomes in how they see themselves. These values are either part of a complex mix of factors or follow from things that could have happened but do not happen. For example, the positive emotions produced during a conversation after a movie, or if someone is prevented from taking their life by hearing a piece of music.[14] We follow Holden's argument and agree with the implementation of a balanced approach. It can be a definition of impact that includes the affective elements of cultural experience, practice and identity, and the full range of quantifiable data. This hybrid approach can help create strong cultural institutions confident in their worth and integrate them into the social fabric rather than existing as an add-on functional tool.

Holden's perspective allows us to re-think the distinction between museums and their public. Instead, we would like to approach their relationship not as a vectorial one - of input and output -but as a rhizome that transverses and entangles with different aspects of the public, with both entities being integrating parts of the same social fabric. Similarly, to the song's impact in avoiding a tragedy, we see the qualitative impact as a powerful tool to break or question the difference perpetuated by the quantitative approach.

We want to go further and suggest that all these discussions still fall short in addressing what we see as a fundamental ontological distinction in the way museums and public(s) are conceptualised. If museums are always already engaged within a world as part of its becoming processes, then the question becomes less about the one-directional impact and more about the modes and quality of such engagement.

To pursue this question further and go beyond the identified distinction, we next turn to a heuristic exercise around the museum's walls. The exercise will also serve as a segway to propose Speculative Design as a useful approach to imagine what the future of such engagement could be and deal with the complexities of the current historical moment.

SECTION 2

The medium is the wall

We propose to conceptually rethink the museum’s walls as the symbolic boundary that binds it to the broader social fabric network. Alternatively, to provokingly reframe them as a kind of connector, to transform them from agents of separation and differentiation towards points of contact and friction which materialise coordinates in the social space. Walls build limits into space, but in doing so, they also concretise space. They make explicit a specific locus in space and thus can mediate action around that materialisation.

To take this further, we are aided by the concept of media by Marshall McLuhan. His fundamental understanding of it is as an “extension of ourselves”. That is anything that extends our existence and our involvement and action within the environment around us. Something of an enabler. A tool or artefact that expands beyond us, communicating and entangling ourselves in something more extensive. The nature of it shapes the contours and the qualities of the extension. This is fundamentally what McLuhan meant with “the medium is the message”. In extremis, anything ever created has this mediatic nature of building a relationship - through communicating a reality, a sense-making of the world - with the outside. In this relationship, the things we create also shape us back and how we behave. We are quiet in a library; it is not a football stadium after all. Likewise, museum walls have their own particular way to convey and frame the reality of what the possibilities of the institution they represent are. So what if we rethink walls in a way that permits us to re-learn and re-understand their boundaries and mapping practices? Suppose the medium is the message, and walls are the media. What message can museum walls convey as connectors in the social fabric network?

By looking at the museum walls as media, we can trace the implications of boundaries and impact to rethink the museum and its social fabric as a bi/multi-directional network. Considering the museum walls as media, we can describe and critically analyse the limits and barriers museums are creating in current practices. In moving further and redefining the relation (and interaction) between the museum and its social fabric, we want to explore how potential visitors move from and through spaces, only to break through these walls. This can only be done via tracing the boundaries and spaces within the rhizome network.

During the residency that gave origin to this paper, we attempted to answer these questions by using an approach capable of going beyond reality. Next, we expand on it and present some of the prototypes resulting from the speculative application of the heuristic exercise of rethinking walls as connectors with their agency.

SECTION 3

Speculative design for disruptive times

In the previous sections, we discussed the ongoing issue concerning the conceptualisation of impact. As we exposed, the museum’s instrumental approach brought with it the privileging of quantitative and economic values. The impact it can produce is one-directional, hence positions the museum as separate from its social fabric. However, we find an alternative for this issue by rethinking the museum’s walls as a medium. This conceptual tool allowed us to design speculative futures beyond the museum’s separation from its social fabric. In this section, we will present our approach to speculative design and three proposals. It is paramount to mention that although a design is immediately thought of as a problem-solving discipline, our suggestions are alternative futures. They are not based on how possible they can be but on pushing the limits through imagination.

Our take on speculative design follows Fiona Raby and Anthony Dunne’s[1]ideas and methods, leading pioneers on critical design. They explain that speculative design thrives on imagination and aims to open up new perspectives. It is a tool to create spaces for debate about alternative ways of being, encouraging people’s creativity via possible scenarios. Therefore, our project consists of possible futures. Each design starts from a “what if” question to break open existing structures and construct a possible experience. We use this methodology to redefine our relationship to reality, namely the museums and their walls. The speculative design allows us to focus on future possibilities rather than creating solutions for a problem. By materialising our imagination, we can centre specifically the (disappearing of a) separation between the museum and its social fabric.

The upcoming proposals are possible futures and are intended to ask questions on what could it encompass if we consider museums walls as a medium. This allowed us to approach museums not only as ivory towers separated from their potential and actual visitors. They stop privileging the quantifiable and distant impact. Instead, they are extensions of ourselves and explore their potential of being ever-going and transformative platforms. Rethinking the museum walls does not physically alter them but analyse and critically re-approach how they build their limits and the “flow” of visitors. In other words, the following questions guided our proposals: Where does the museum begin and ends? How do potential visitors move and interact with it? How can digital tools help us to elaborate this conceptually and practically?

Possible future #1: Curating Windows

This proposal tackles the issue of the limits of the museum quite literally. Thanks to speculative solar flare technology attached to the glass, the windows can also behave like screens. This allows the building’s facade to transform into itinerant artworks from the museum’s digital works collection. Furthermore, the images will change through the inhabitants’ either conscious or unconscious contribution. The artworks are selected and vary depending on the people’s conversations, actions and emotions. New inorganic and organic technologies and bionic have brought about a more expansive stretch of the museum boundaries regarding location and participation. Where is this museum, and who is a part of it?

This proposal dismantles the limits of the museum and positions it as a multi-local institution. This means that this museum is no longer contained by physical walls and is not curated solely by appointed curators. Any window can become an exhibition wall (or screen), and any inhabitant can become a curator. The display of images responds to the viewer/curator’s embodied responses; thus, we can state that the exhibition reflects their vital pulsations and affects. This museum allows the spectators to open up and actively build their social fabric in different ways. They can expand towards the walls and personalise the spaces they usually dwell in.

︎︎︎

Image 1: CURATING WINDOWS by Danique

Hofstee

︎︎︎

Image 1: CURATING WINDOWS by Danique

Hofstee

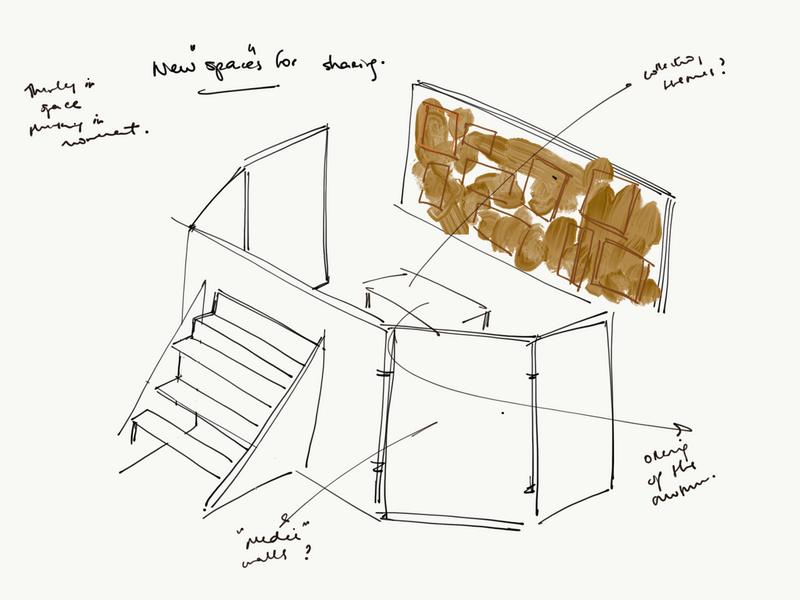

Possible future #2: A Round-table in the City: The agora whiteboard

This speculation is driven by the idea that museum walls did not wholly change in shape. Still, they open up into and within the city. The museum is expanded and becomes a sort of mobile set of walls that passers-by can interact with. These walls can be used as ephemeral gathering places for debate. They are no longer fixed spaces for visiting and safeguarding. Instead, they focus on the visitor’s flux, movement and ever-changing interaction. They enable a free dance between the artworks and the visitors. Space no longer commands the museums’ essence but the way they make visitors flow and interact in the events they create. They are non-places-like museums.

Therefore, every citizen becomes a potential visitor, and the whole city is a possible museum. Museums no longer bother with bringing the citizens inside their walls, classifying them by visitors or non-visitors. Museums open up and interweave themselves into the social fabric impacting it in different quantitative and qualitative levels. They are as flexible as the “visitors” needs and demands of the institution. This museum does not focus on containing and sharing, but they are moved by movement. They are guided by the dance-like interaction citizens perform between them.

︎︎︎ Image 2: A ROUND-TABLE IN THE CITY by Jose Hopkins

Possible future #3: The Museum Pill

This speculation is coming forth from questioning the boundaries of the body as an object. The Museum Pill is proposed to be a wholesome experience of the human embodiment where the user is immersed in an unexpected piece. The pill literally transcends borders of physicality. It will activate the senses, transporting the pill-taking individual into an entanglement of sounds, scents and colours capable of shifting perspective and opening horizons of possibilities. Temporarily, perception becomes infiltrated to a point where the user revels in an altered existence, breaking the limits, and expanding the intersection between body and art. This experience is the ultimate free art journey, where the museum is projected in hyperspace.

Thus, this proposal allows for the body itself to become a space for exhibiting art. It also shows that art objects are part of how we see the world and how we see ourselves in the world. Art is no longer contained within the museum walls, but it is part of the participant/visitor/user. It becomes impossible to tell apart the artwork from the visitor, thus its social fabric. In this design, it is clear how museum walls have become an extension of ourselves, how they transform us in return and affect our behaviour. Like a stadium makes us have strong emotions and bonds with the teams playing. The museum pill persuades us to temporarily shift experience our relationship with the world.

︎︎︎ Image 3: MUSEUM ARNHEM PILL by Danique Hofstee

CONCLUSION

As we have shown in this paper, there is an essential issue with solely using quantitative values to understand the museum’s impact. This method privileges a one-directional and cause-effect perception of impact. We demonstrated that this approach affects how museums position themselves within their social fabric. It places them as separate and even ontologically different. This perspective, framed within the functionalist approach, privileges a type of impact and an understanding of social change and well-being based on measurable data. Furthermore, it overlooks the potential unmeasurable effects that museums have, which are as important as the others.

As an active response to this issue, our project consisted of envisioning and proposing speculative futures. Starting from the premise that it is imperative to see museums as intertwined with their social fabric, we suggested a series of scenarios that break open the existing institutional structures. When we envision museums as already entangled within the world, the question becomes less about how museums produce impact and more about their engagement quality.

We employed a speculative design approach guided by what if we consider the museum’s walls as media. This heuristic exercise resulted in a series of designs addressing possible futures that dismantled the museums’ limits and merged them with society’s ever-growing transformations. It allowed us to re-approach the infrastructure network museums are part of, taking into account the use and relations between technologies, societal issues and art. This design approach allowed us the rethink the network the museum walls are part of. Instead of merely considering their artefactual nature – a building with walls and works inside those walls – we use them to look beyond the established parameters of impact.

We believe this approach and these speculative designs prove fruitful in reconsidering the institution’s position and relations within society. Although we know these proposals are perhaps too radical, they may lack a situated approach and are not applicable shortly; we believe we proved their usefulness in getting new synergies started. We hope this paper motivates further research on museum studies’ speculative approaches, namely how museums understand their relationship with its immediate (and not so immediate) context.

For instance, as possible further research, we believe there is potential in exploring who and where this ‘social fabric’ is. The more museums are turning towards the digital and applying these logics to their institutional work; we believe the idea of ‘immediate context’ will change. In other words, the social fabric where the museum is entangled will transform. We believe there is an exciting potential for our approach to bringing light to this issue.

[1] Scott, Carol. “Museums and Impact.” Curator - The Museum Journal 46, no. 3 (2003): 293-310

[2] Holden, John. Capturing Cultural Value. How culture has become a tool of government policy. London: Demos, 2004

[3] Kelly, Linda. “Measuring the impact of museums on their communities: The role of the 21st century.” ICOM International Committee for Museum Management (INTERCOM) 2006. Taipei, 2007

[4] Jowell, Tessa. Government and the Value of Culture. London: Department for Culture, Media and Sport, 2004

[5] Marshall, Alex. “What is a museum? A dispute erupts over a new definition.” New York Times. 2020

[6] Jones, Johanna. “What problem in our community is our museum most uniquely equipped to solve?” Medium. 2019

[7] Sanderhoff, Merete. “Statens Museum for Kunst: The social impact of using art to increase civic participation of young people, 2018.” Europeana.2019

[8] Holden, Capturing Cultural Value.2004:26

[9] Holden, Capturing Cultural Value.2004:19

[10] Kelly, “Measuring the impact of museums on their communities” 2007; Scott, Carol. “Museums: Impact and value.” Cultural Trends 15, no. 1 (2006)

[11] Scott, Carol. “Museums: Impact and value.” 2006: 47

[12] Jowell. Government and the Value of Culture. 2004

[13] Holden, Capturing Cultural Value.2004:22

[14] Holden, Capturing Cultural Value.2004:18